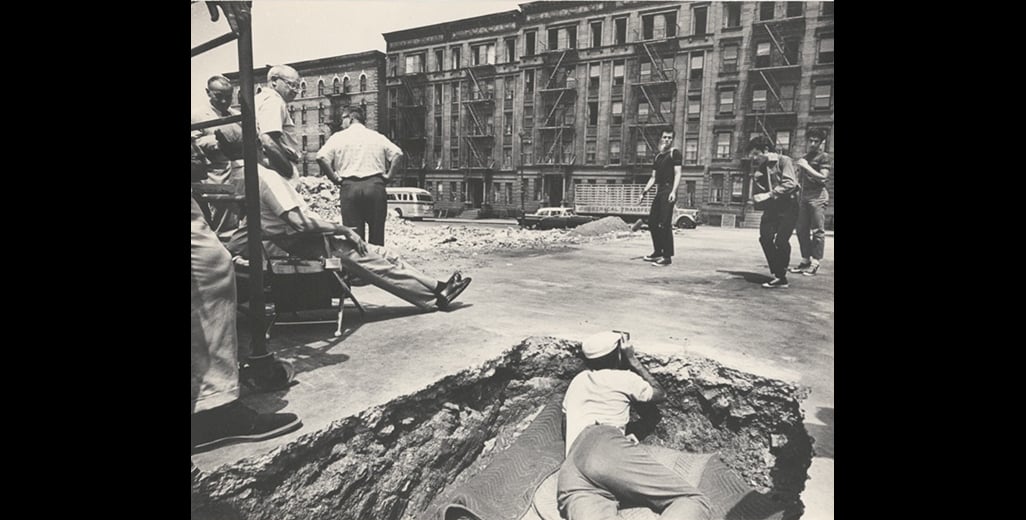

Pre-production location shooting for the film

Photo: Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library

The Ground Beneath West Side Story

The Ground Beneath West Side Story

August 21, 2023

by Julia Foulkes, Professor of History at the New School

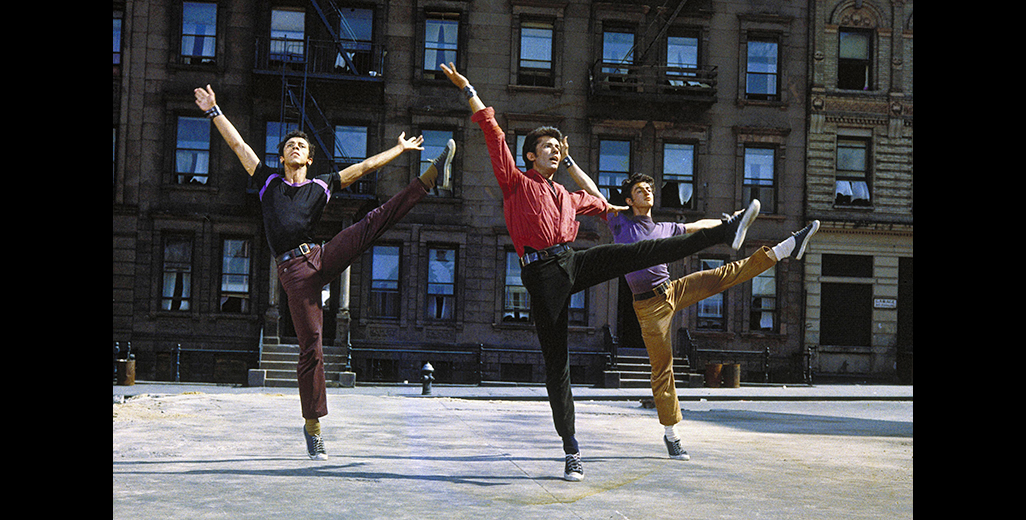

The demolition site for the Lincoln Square Urban Renewal Project was an outdoor soundstage for the filming of West Side Story in August 1960. A portion of the fourteen-block area west of Central Park razed for construction of middle-class housing, a performing arts center, and a new campus for Fordham University offered unusual perspectives for camera angles. The directors shoveled a shallow hole for the camera so that it could capture the dancers from below, as they reached to the sky with arms and legs spread wide. The flattened parts of the site were an ideal dance floor. And the blocked-off streets and nearly demolished brownstones on west 70th Street made for a realistic backdrop for the Jets and Sharks’ first encounters in the opening scenes of the film.

Jets and Sharks danced on grounds that held rooming houses filled with Irish porters, German elevator operators, and Puerto Rican families just months earlier. Churches bursting with Caribbean immigrants, the estates of wealthy white property owners, and Lenape trading trails preceded them.

The stage and film productions of West Side Story drew inspiration from the San Juan Hill neighborhood and its layers of history—celebrating while also distorting it—in a mix of love and theft, acknowledgment and erasure, contemplation and damage.1 From its depiction of urban areas to its portrayal of Puerto Ricans, West Side Story created a tale of the neighborhood that endures.

Why was this area of the city chosen for the story?

The west side of Manhattan was newly in the news in 1955 when the creators began working in earnest on a musical based on updating Shakespeare’s Romeo & Juliet. Planning Commissioner Robert Moses had begun publicizing his latest urban renewal plan with an arts center that would be at the heart of it. So, too, in the news was the dramatic increase in the number of people moving from the island of Puerto Rico to New York City. West Side Story married an old tale with current headlines, a universal theme of love across boundaries played out in a specific racially-charged iconic American city.

The creators of West Side Story—choreographer and director Jerome Robbins, composer Leonard Bernstein, playwright Arthur Laurents, and lyricist Stephen Sondheim—did not grow up or live in San Juan Hill; they were not Puerto Rican. Their backgrounds corresponded more with the initial idea for the conflict to be between Jews and Catholics on the Lower East Side. East Side Story, as they dubbed it, more closely reflected their personal experiences with prejudice. Being Jewish had shaped their lives and that of their parents, some of whom were immigrants. Anti-Semitism, as well as the criminality of their homosexual desires then, prompted interest in exposing the discrimination and injustice that lurked within the American dream.

The Lower East Side locale made sense for the story of their generation having come of age between the world wars, or even their parents’. The number of Jewish immigrants to that area in the beginning of the 20th century received media attention and concern regarding assimilation. But was this the conflict and the place for a story about the city of the 1950s?

East Side Story relocated to West Side Story via Los Angeles. When Robbins prompted his collaborators to think again about the Romeo idea, Bernstein and Laurents were both in Los Angeles. (Sondheim would join the team months later.) Bernstein was conducting a five-concert series at the Hollywood Bowl called the “Festival of the Americas,” with music from the U.S., Mexico, Central and South America. Laurents was plying his skills in writing screenplays.

Current L.A. newspaper headlines about gang violence, particularly between Chicanos and whites, caught their attention. What about placing an updated Romeo & Juliet in L.A.? That got something right—a volatile new ethnic prejudice amongst youth rather than religious conflict or family feuds. But Laurents claimed that he did not know anything about L.A.2

They turned their gaze eastward, to their home of New York, and made an analogous leap: gang violence between Puerto Ricans and whites (even though much gang violence in New York was not so cleanly segregated).3

This set minds whirring. If Laurents was uneasy about his scant knowledge of L.A., he expressed no such concern about Puerto Ricans, perhaps a first indication of the play’s loose grasp of its topic. Laurents promptly wrote a new outline, with some characters identified and named, such as Bernardo (Tybalt), Anita (a revision of Shakespeare’s Nurse), Doc (“possibly a Jew”), and mambo and jitterbugging central to the action.4

The inspiration of Los Angeles stood behind the setting in New York. A city with overt Mexican influences, L.A. was undergoing massive infrastructural changes as highways expanded and diffused the urban core. Seeing New York from the perspective of Los Angeles not only highlighted the noticeable influx of Puerto Ricans that occurred in the 1940s and ‘50s; it prompted a reckoning with the dramatic physical transformations in the landscape of the city.

So what area stood out when looking at New York from Los Angeles? San Juan Hill—just identified by Robert Moses as in need of urban renewal.

Jumping to the west side for their revised tale might have prompted the creators to delve into research about the neighborhood. But theirs was a fuzzy vision of the area as a stand-in for more general changes in the city. Puerto Ricans, in fact, were populating many areas in addition to San Juan Hill—including the Lower East Side.

The west side the creators wanted to capture was the vulnerability of place and people.

Just prior to the opening of the Broadway show, Laurents noted that the building in which the first meetings about the idea had occurred had come down. Then the building in which the group renewed their efforts years later also disappeared, this one even sooner on the heels of their occupancy.5 Robbins noted the same impermanence when scouting the city for film locations in early 1960: “We’re pretty sure that the backgrounds we’ve photographed around here will still be standing [when shooting for the film begins in a few months], but who can tell?”6

Moses looked at impoverishment in San Juan Hill as cause for demolition and opportunity to create an entirely new neighborhood ordered by gleaming sleek buildings—for more wealthy and whiter residents that would move to the neighborhood for the new amenities.

The creators of West Side Story, instead, saw deprivation, conflict, and longing. This was the ground for a tragic love story with skyscraper-high stakes—a musical filled with vivacious song and dance with two people killed by intermission and another dead at the end.

West Side Story keyed Romeo & Juliet to contemporary New York by adding ethnic prejudice to the plot. Unlike the Shakespeare play in which mixed messages and poor timing result in a double suicide of the lovers at the end, the musical finishes with only one of the lovers dead. And that death is prompted by a racist and sexist assault. On behalf of Maria, Anita carries a message to Tony at Doc’s drug store—she still acts on the belief that love can overcome bigotry even after the loss of her own lover to that hatred. But the assault prompts her to change her message to Tony. She lies that Chino has killed Maria. Tony rushes out to the street, beseeching Chino to kill him as well.

It’s discrimination that causes death. West Side Story reanimated a long-cherished story with a condemnation of current-day bigotry.

And yet the musical also perpetuated ethnic stereotypes and a distorted view of the city.

The story’s relation to its neighborhood was at the root of the misrepresentations. Jets and Sharks danced on the open graves of layers of displacement and exploitation in San Juan Hill. The ghosts and bones of Native Americans, enslaved peoples, immigrants, working classes were entombed here.

On that same land, the Jets sang an anthem to claiming one’s place. “Yeah! And we’re going beat/Every last buggin’ gang/On the whole buggin’ street!,” the Jets declared in the opening number.

The creators did not seek—nor did they supply—a footnoted portrayal of San Juan Hill. In fact, when a producer prodded playwright Laurents to spend a week “observing these kids at work and play” to enhance the realism of the script, he balked. A “socioeconomic history of the neighborhood” was not needed, Laurents claimed; “I think the reality should be an emotional, not a factual one.... The point is prejudice and that is the background of the plot,” he declared.7 The musical’s connection to the streets was in theme, for Laurents, not in a detailed description of the environment.

A similar slipperiness was part of the song and dance as well. After missing an exit off the Henry Hudson Parkway, Leonard Bernstein got his idea for the music. As he drove under a causeway around 125th street, all around him “Puerto Rican kids were playing, with those typical New York City shouts and the New York raucousness,” he remembered. It was in the contrast between that liveliness and the backdrop of the causeway with its concrete pillars and Roman arches that Bernstein found his theme: “contemporary content echoing a classic myth.” “Suddenly I had the inspiration for the rhumba scene,” he realized.8 The music was neither about who had originated the rhumba nor a scene from San Juan Hill.

Robbins scoured the city for dance inspiration. He left his office on 74th St. and Lexington Avenue and walked twenty blocks north to a world where “the streets are darker, the signs are in Spanish, and the people lead their lives on the sidewalks,” Robbins explained.9 It is “absolutely like going into a foreign country,” he wrote.10 A journalist prodded him on the obvious contradiction: how insulated was he in his own world that he did not know about this growing part of the city? “But I hadn’t really seen it,” Robbins defended.11

The repartee revealed the segregation that slashed the city into parts, one often hidden from another. The creators incorporated into the musical this exploration of how separate worlds could exist so close to one another, whether Puerto Rican and white or, by extension, gay and straight, Jewish and Gentile, immigrant and self-fashioned American. The production exemplified the around-the-corner quality of life in New York: separated and yet inextricably connected.

Art often achieves exactly this kind of recognition of connection. For many, though, West Side Story widened rather than bridged this separation. Scholars—especially those in Puerto Rican Studies—have documented the skewed portrayal of Puerto Ricans in the production.12 An “Olé!” and flamenco moves reminiscent of a Spanish bull fight rather than anything resembling Puerto Rican song and dance in the middle of the song “America” makes the point. There was no fidelity to cultural accuracy, even if the story also proclaimed the often-overlooked political point that Puerto Ricans were U.S. citizens. The film carved deeper—and spread globally—harmful stereotypes of Puerto Ricans as vengeful knife-wielding men and sexy skirt-swishing women. A story meant to confront prejudice instead perpetuated it.

The changing conditions of San Juan Hill served the makers of West Side Story with fertile terrain to mine. The tumultuous visions of past and future—forced removal and demolition for a city yet to be—fit the yearning and tension of young lovers from different sides of the battle to belong in a callous, demanding place. Their “Somewhere” does not exist in this west side, neither in the past nor a renewed future.

The creators used San Juan Hill to fit this theme rather than adhere to any of its distinctive elements. There is almost no representation of the mixture of people that lived side-by-side. One Black person stands at the back of the film’s dancehall scene; there is nothing that conjures up the rooming board houses on W. 63rd Street with tenants from Puerto Rico, Hungary, Ireland, and other U.S. states. The cultural traditions of Caribbean immigrants, African Americans, and—most glaringly, Puerto Ricans—are largely absent. There isn’t a whiff of the rich cultural life of the neighborhood that nurtured Thelonious Monk or embraced the premiere of Shuffle Along with music and lyrics by Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake at a theater on 63rd Street.

An indistinct west side blurred San Juan Hill itself.

Perhaps more than any other art form, a musical is a fantasy. We don’t typically burst into crafted song and choreographed dance to express our emotions. And yet the power of that genre is exactly that leap. The fantastical elements transport us to a truer emotional reality.

For many, West Side Story achieved that effect. But the fantasy relied on falsity. Inspiration is a ground from which to imagine. What happens when inspiration abets ignoring? Erasure? Appropriation? Among the legacies of San Juan Hill, West Side Story leaves us grappling still with these questions.

Notes

1 Eric Lott, in Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class (NY: Oxford University Press, 1993), argues that cultural appropriation—usually that of whites taking from people of color—includes praise and envy (love) even as it also often lampoons, misshapes, and plunders (theft).

2 Decades after the fact, Laurents claimed that he could only have written “movie Chicanos” and insisted on the transfer to the “New York and Harlem I knew firsthand, and Puerto Ricans and Negroes and immigrants who had become Americans”; Arthur Laurents, Original Story By (NY: Knopf, 2000): 337-38. He does not detail how he knows these stories firsthand.

3 See Eric C. Schneider, Vampires, Dragons, and Egyptian Kings: Youth Gangs in Postwar New York (NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999) and Robert W. Snyder, “A Useless and Terrible Death: The Michael Farmer Case, ‘Hidden Violence,’ and New York City in the Fifties,” Journal of Urban History 36.2 (2010): 226-50.

4 Arthur Laurents, “Romeo,” n.d. [1955], b.81 f.1, Jerome Robbins Papers, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

5 Arthur Laurents, “The Growth of an Idea,” New York Herald Tribune (4 August 1957): Sect. 4, 1.

6 Jerome Robbins quoted in [no author], “Small Rumble,” New Yorker (2 April 1960): 35.

7 Arthur Laurents to Cheryl Crawford, n.d. [April 1957?], b.43 f.2, Roger Stevens Papers, Library of Congress. See also Laurents, Original Story By: 328; “Landmark Symposium: West Side Story,” a conversation with the four creators in Dramatist Guild Quarterly v.7 #3 (1985).

8 Leonard Bernstein quoted in Meryle Secrest, Leonard Bernstein: A Life (NY: Knopf, 1994): 212.

9 David Boroff, “Preparing the West Side Story,” Dance Magazine v.31 #8 (August 1957): 14-19; quote 15.

10 Jerome Robbins to Tanaquil LeClerq, 25 February 1957, Tanaquil LeClerq Papers, New York City Ballet Archives.

11 Robbins quoted in Boroff, “Preparing the West Side Story”: 15.

12 See the work of Alberto Sandoval-Sánchez, Frances Negrón-Muntaner, Deborah Paredez, Brian Herrera, and Ernesto R. Acevedo-Muñoz.