NYC Parks Photo Archive

English

Spanish

A History of the Black Community in San Juan Hill: 1900-1915

Una historia de la comunidad negra en San Juan Hill: 1900-1915

January 30, 2023

by Marcy S. Sacks, Professor of History at Albion College

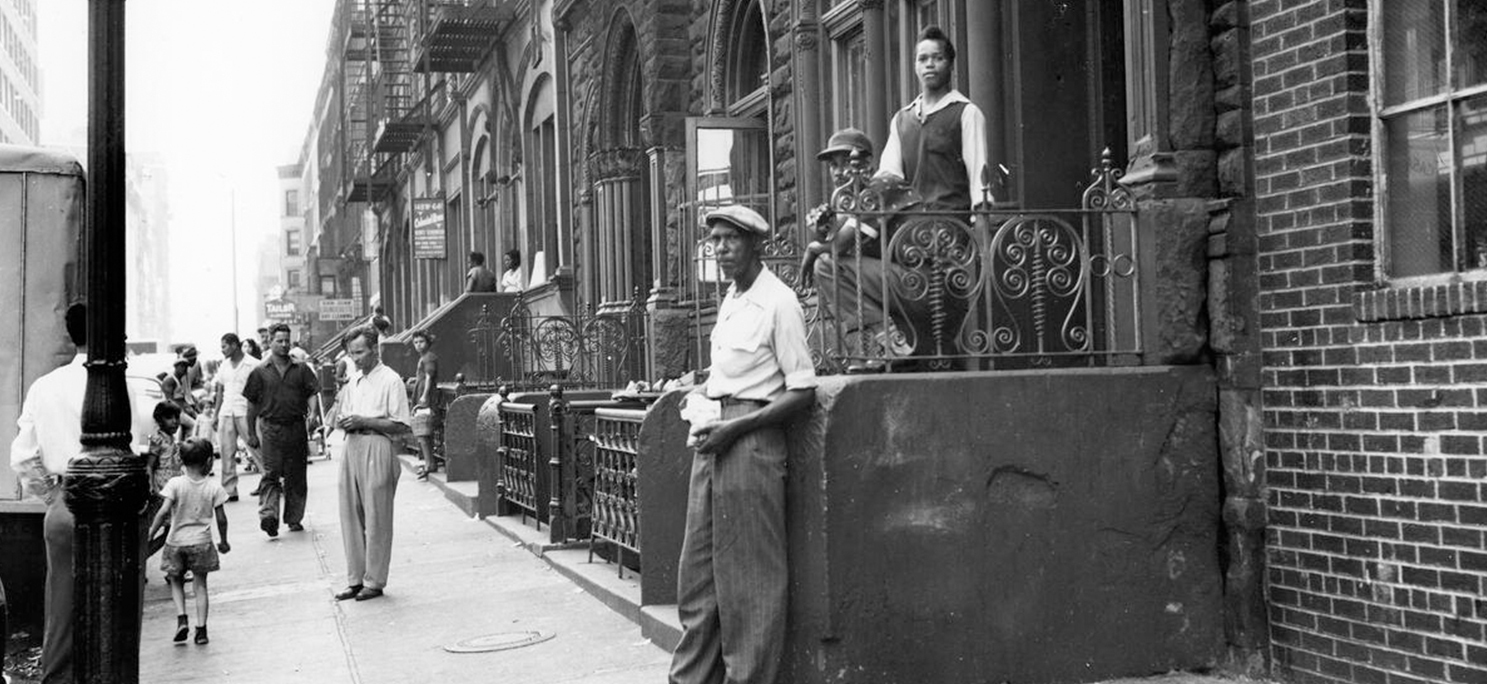

At the turn of the 20th century, Manhattan’s Upper West Side was abuzz with activity. The neighborhood of San Juan Hill and its surrounding environs housed a predominately Black population that hailed from every part of the United States and Caribbean, creating an incredibly cosmopolitan community.1 Evidence of that diversity abounded: in the ethnic food offered at restaurants and groceries, in the variety of clothing styles on display, in the mix of religious denominations and preaching styles from which church-goers could choose, and in the array of languages and accents heard out in public.

The members of this population had come, like so many other migrants and immigrants, to both escape conditions at home and to experience all of the excitement and opportunities that New York City had to offer. A steady stream that began with a trickle at the end of the Civil War and steadily rose in the ensuing decades led to dramatic growth in the Black population; by 1900 it had burgeoned to over 60,000, a more than four-fold increase in thirty years. Well over half of that number had been born outside of the New York.2

The mixing of people from all economic classes and so many ethnic backgrounds into a small geographic space transformed this handful of city blocks into a multicultural representation of the African diaspora.

A principios del siglo XX, el Upper West Side de Manhattan rebosaba de actividad. El barrio de San Juan Hill y sus alrededores albergaban una población predominantemente negra procedente de todos los rincones de los Estados Unidos y del Caribe, lo que creaba una comunidad increíblemente cosmopolita.1 Abundaban las pruebas de esa diversidad: en la comida étnica que se ofrecía en los restaurantes y las tiendas de comestibles, en la variedad de estilos de ropa que se exhibía, en la mezcla de denominaciones religiosas y estilos de culto entre los que podían elegir los fieles, y en la variedad de idiomas y acentos que se oían en la calle.

Los miembros de esta población habían llegado, como tantos otros emigrantes e inmigrantes, tanto para escapar de las condiciones de sus países como para experimentar toda la actividad y las oportunidades que ofrecía la ciudad de Nueva York. Al final de la Guerra Civil, se produjo un flujo constante de inmigrantes que no dejó de aumentar en las décadas siguientes, lo que condujo a un crecimiento espectacular de la población negra, que en 1900 había superado los 60,000 habitantes, lo que suponía un aumento de más de cuatro veces en treinta años. Mucho más de la mitad de esa población había nacido fuera de Nueva York.2

La confluencia de personas de todas las clases económicas y de múltiples orígenes étnicos en un pequeño espacio geográfico transformó este conjunto de manzanas en una representación multicultural de la diáspora africana.

The sociologist and first secretary of the NAACP, Frances Blascoer, described a city scene: “one finds a newly arrived family from the West Indies eagerly and perilously hanging out of fourth story windows to view the strange street life of their adopted city…From one apartment come the strains of a Bach fugue being practiced by the daughter of an established merchant of the neighborhood…Still another few steps discloses a front stoop alive with children and a bandanaed ‘Auntie’ fresh from the South. Sandwiched among these is the New York Negro family, thoroughly and typically American in its mode of life and ideals.”3 Such a milieu became an incubator for rich cultural development.

La socióloga y primera secretaria de la NAACP, Frances Blascoer, describió una escena de la ciudad: “Aquí puedes encontrar a una familia recién llegada de las Indias Occidentales que se asoma ansiosa y peligrosamente a las ventanas del cuarto piso para contemplar la extraña vida callejera de su ciudad de adopción… Desde un apartamento se escuchan los acordes de una fuga de Bach que practica la hija de un comerciante establecido en el vecindario… Y apenas unos pocos pasos más adelante, hay una tía con un pañuelo en la cabeza, recién llegada del Sur, acompañada de un montón de niños. Aquí también se encuentra la familia negra de Nueva York, absolutamente estadounidense en su modo de vida y en sus ideales”.3 Este contexto se convirtió en una incubadora de un rico desarrollo cultural.

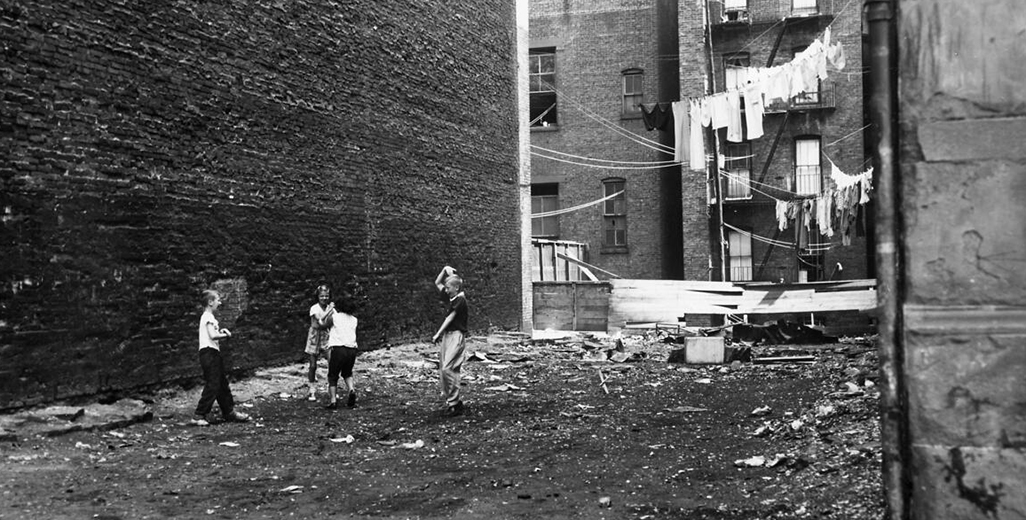

But it also reflected residential realities. Racial intolerance among Manhattan’s white residents grew in tandem with the increase in the number of Black residents. Increased harassment by whites pushed the city’s Black population into ever-more-limited residentials spaces. The relentless march northward would eventually end in Harlem, but before they made it that far, San Juan Hill claimed the bulk of this community. For a time, it was one of the most congested neighborhoods in New York; one block alone housed nearly five thousand residents.4 Mary White Ovington, a founding member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, characterized the overcrowded tenements as “human hives, honeycombed with little rooms thick with human beings.”5

Unlike the European immigrant experience in which subsequent generations could translate economic advances into geographic mobility, residential restrictions faced almost exclusively by Black people forced all classes into close quarters. The relatively well-to-do intermingled with the people living in poverty in San Juan Hill, as the journalist J. Gilmer Speed noted in 1900. The “virtuous and vicious live so near to one another that they elbow each other,” he wrote. “It has long been a problem,” the New York Age corroborated eight years later, “to separate the hoodlum element from the respectable class of colored people.”6 Doctors, artists, teachers, elevator operators, sex workers, preachers, domestic workers, thieves, and the unemployed all found themselves sharing cramped neighborhood space in San Juan Hill, with no group able to escape the influences of the others. Mary White Ovington vividly described the district’s mass of humanity: “There were people who itched for a fight, and people who hated roughness. Lewd women leaned out of windows, and neat, hard-working mothers early each morning made their way to their mistresses’ homes. Men lounged on street corners in as dandified dress as their women at the wash tubs could get for them; while hard-working porters and longshoremen, night watchmen and government clerks, went regularly to their jobs.”7

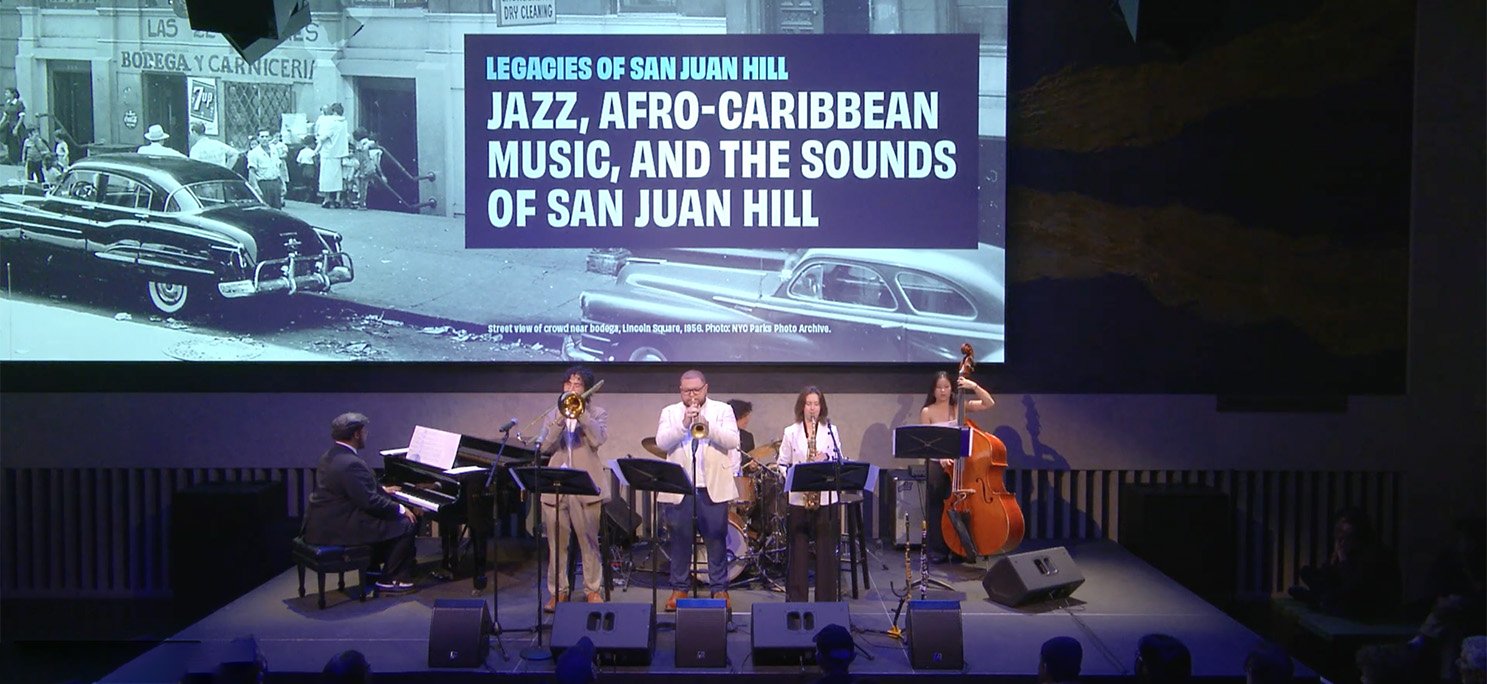

Despite the challenges, the density of the population in San Juan Hill provided the benefit of concentrating the organizations and services that catered to Black people. For many, especially the younger crowd, the night scene held the greatest allure. “The only recreation we had [down South] was prayer meeting and little parties,” one migrant explained, but New York promised dances “every Saturday night.”8 San Juan Hill did not disappoint. Dozens of poolrooms and bars sprang up in the neighborhood. Pleasure-seekers could find gambling clubs and poker clubs, professional clubs and sporting clubs. Rathskellers in tenement basements offered to a working-class clientele inexpensive alcohol, usually a pool table, and sometimes music that ranged from “a wheezy old accordion” to pianos and drums. “Sailors, laborers, thieves, shoestring gamblers, and wretches” could be found “whirling around the floor” until dawn. These informal dance halls became thriving social centers.9

Meanwhile, upscale venues like the Marshall Hotel that hosted bands during the dinner service contributed to the emergence of a Black bohemia in San Juan Hill. Musicians and vaudevillians such as James and Rosamond Johnson, Harry T. Burleigh, Will Marion Cook, Bert Williams, and Bob Cole flocked to the area, and nights at places like the Marshall, in “the gay air of the dining room” with live music playing and “crowds of well-dressed colored men and women lounging and chatting in the parlors, loitering over their coffee and cigarettes while they talked or listened to the music,” generated tremendous creative energy.10 James Weldon Johnson claimed that the Marshall hosted the first modern jazz band to play in Manhattan. Called the Memphis Students, the orchestra used a combination of banjos, saxophones, clarinets, and tap drums to forge the new sound.11

Though migrants and immigrants both admitted that they worshipped less frequently in New York than they had at home, the church still remained the center of Black life. As the neighborhood expanded, so too did the number of institutions that served its population. St. Mark’s Methodist Episcopal, Mount Olivet Baptist, and St. Benedict the Moor churches all opened new buildings just south of San Juan Hill. Scores of storefront churches dotted the landscape appealing to the particular customs of newcomers from the South and Caribbean. Union Baptist Church, for example, led by the Reverend Dr. George H. Sims of Virginia, gathered the “very recent residents of this new, disturbing city” and made Christianity “come alive Sunday morning” with a “southern style” of service. It became known as a “shouting church.” Similarly, St. Cyprian’s Chapel, an Episcopal church built in the early twentieth century in San Juan Hill, appealed to Caribbean-born worshippers.12 On any given Sunday, observers might see sumptuous outfits on display as church-goers walked to services. “White gloves and fine raiment” prevailed, according to one witness. Black men often sported a dark suit, “black derbies, black or dark brown or dark grey overcoats, and in many cases…canes.” Women could be seen in brightly-colored dresses and elaborate hats.13

Beyond meeting the spiritual needs of their members, religious institutions also provided social opportunities with activities like summer excursions outside of the city, picnics, concerts, and lectures. Churches offered aid to the needy, could be found at the forefront of social justice efforts, and they often led efforts at racial uplift. Pastors frequently attempted to intervene with the courts when church members faced criminal prosecution. Others took to neighborhood streets to preach against vice. The ministers of St. Cyprian’s Episcopal Church and the Union Baptist Church, both located in San Juan Hill, significantly contributed to the reduction in the number of “dens and clubs” in the area.14

A wide variety of other organizations emerged to provide support and social activities to the neighborhood’s Black residents. The YMCA opened just south of San Juan Hill at the end of the nineteenth century, offering a “home” to “every young man in the South…where he can come and find friends.”15 The Grand United Order of Odd Fellows, the Colored Freemasons, and the Negro Elks” formed in this period as well and put their headquarters in the neighborhood. Caribbean immigrants organized cricket teams and tennis clubs, while southerners actively participated in baseball. And while white outsiders typically saw a homogeneous population, Black New Yorkers highlighted their differences by forming groups like the Society of the Sons of New York, the Sons and Daughters of South Carolina, the Sons of North Carolina, the Sons of Virginia, the Bermuda Benevolent Association, the Cubans’ Society of Thirty, the Danish West Indian Ladies Aid Society, and the Montserrat Progressive Society.16

Small merchants found their niche by catering to particular ethnic preferences. Immigrants and migrants sought to recreate a sense of home through their cooking, and both restaurants and grocers helped to fulfill those desires. Rosanna Weston, a life-long resident of the Phipps Houses, a model tenement for working-class Black families that opened on West 63rd Street in the heart of San Juan Hill early in the twentieth century, remembered her immigrant mother’s cooking. “There were a couple of colored merchants on our block who sold West Indian things,” she recounted, including cornmeal and codfish, not common ingredients in American grocery stores. Her mother would create a meal called “fungie.” “I wasn’t crazy about it,” Weston admitted, “but we ate plenty of it.”17 Similarly, restaurants often hosted special meals featuring southern or Caribbean delicacies like collard greens and sweet potatoes, using nostalgia and homesickness to boost patronage.18

Neighborhood life was also characterized by animosity from surrounding white communities. The New York Central Railroad’s open tracks, “which maimed black and white impartially,” offered neutral ground between Black residents and “white enemies” to the west. Rosanna Weston’s parents warned her away from the Irish side of the street. “That was forbidden territory. You weren’t supposed to go over there. They used to come over on this side and they would fight.”19 But it was nearly impossible to avoid the violence. An anonymous informant wrote to Mayor Mitchell in 1914 to complain about “a bunch of white boys” who roamed the district demanding money from any Black passerby. Refusal to pay resulted in physical retribution; one woman had been struck over the head with a milk bottle.20

Racism and harassment from whites led Black New Yorkers to learn to rely on each other, and within their community in San Juan Hill, they did just that. Neighbors helped neighbors – they watched each other’s children, they opened their homes to people who needed a place to sleep, and they rallied around those who faced troubles. Strangers quickly became fictive kin, offering guidance on the mysteries of urban life and a sympathetic ear when loneliness crept in. Southern and Caribbean newcomers made their homes “among familiar faces,” helping to create discrete enclaves within San Juan Hill’s crowded streets. “The housewife who timidly hangs her clothes on the roof her first Monday morning in New York is pleased to find the next line swinging with the laundry of a Richmond acquaintance, who instructs her in the perplexing housekeeping devices of her flat,” wrote Mary White Ovington. “To find the girl you knew at home, in the pew next to you, is still more delightful when you have arrived tired and homesick, at the great city of New York.”21 In this way, Black newcomers to New York recreated a sense of home and constructed a place of belonging in an adopted city. But it was the incredible diversity of the San Juan Hill community with its myriad of languages, heritages, ideas, and traditions that helped to spark the creative ingenuity that would soon produce the Harlem Renaissance and make New York City into the cultural capital of Black America.

Pero también reflejaba las realidades de sus habitantes. La intolerancia racial entre los residentes blancos de Manhattan creció a la par que el aumento en la cantidad de residentes negros. El mayor hostigamiento por parte de los blancos empujó a la población negra desde la ciudad hacia espacios residenciales cada vez más limitados. La incesante marcha hacia el norte eventualmente terminaría en Harlem, pero antes de llegar hasta allí, la mayor parte de esta comunidad se asentó en San Juan Hill. Durante un tiempo, fue uno de los barrios más concurridos de Nueva York; una sola manzana albergaba a casi cinco mil residentes.4 Mary White Ovington, miembro fundadora de la Asociación Nacional para el Progreso de las Personas de Color, calificó las viviendas superpobladas de “colmenas humanas, con pequeñas habitaciones repletas de personas”.5

A diferencia de la experiencia de los inmigrantes europeos, en la que las generaciones posteriores podían transformar los avances económicos en movilidad geográfica, las restricciones residenciales a las que se enfrentaban casi exclusivamente los ciudadanos de raza negra los obligaban a vivir confinados independientemente de la clase social. Las personas relativamente acomodadas se relacionaban con quienes vivían en la pobreza en San Juan Hill, como señaló el periodista J. Gilmer Speed en 1900. “Los virtuosos y los viciosos viven tan cerca unos de otros que casi se rozan codo con codo”, escribió. “Hace tiempo que esto representa un problema”, corroboró el New York Age ocho años más tarde, “hay que separar a los rufianes de la clase respetable entre la gente de color”.6 Médicos, artistas, profesores, ascensoristas, trabajadoras del sexo, predicadores, empleadas domésticas, ladrones y desempleados se encontraban compartiendo el espacio reducido del barrio de San Juan Hill, sin que ningún grupo pudiera escapar de las influencias de los demás. Mary White Ovington describió vívidamente la aglomeración humana del distrito: “Había gente con ganas de pelear y gente que odiaba la violencia. Las mujeres lascivas que se asomaban a las ventanas, y las madres pulcras y trabajadoras se cruzaban cada mañana en el camino hacia las casas de sus patronas. Los hombres holgazaneaban en las esquinas con la vestimenta más elegante que las mujeres de los lavaderos podían conseguirles, mientras que los cargadores y estibadores, los vigilantes nocturnos y los funcionarios públicos acudían regularmente a sus puestos de trabajo”.7

A pesar de las dificultades, la densidad de la población en San Juan Hill ofrecía una gran ventaja: concentraba las organizaciones y los servicios que prestaban atención a las personas de raza negra. Para muchos, especialmente para los más jóvenes, la escena nocturna era muy atractiva. “La única recreación que teníamos \[en el Sur] era la reunión de oración y pequeñas fiestas”, explicaba un emigrante, pero Nueva York prometía bailes “todos los sábados por la noche”.8 San Juan Hill no decepcionaba a nadie. En el barrio surgieron montones de salones de billar y bares. Quienes buscaban diversión podían encontrar desde clubes de apuestas y de póquer, hasta clubes para profesionales y clubes deportivos. Los bares situados en los sótanos de las viviendas ofrecían a clientes de la clase trabajadora alcohol barato, por lo general una mesa de billar y, a veces, música que iba desde “un acordeón desafinado” hasta pianos y percusión. “Marineros, obreros, ladrones, apostadores de poca monta y desdichados” podían encontrarse “dando vueltas” hasta el amanecer. Estos salones de baile informales se convirtieron en prósperos centros sociales.9

Mientras tanto, locales de lujo como el Marshall Hotel, que recibía bandas de música durante la cena, contribuyeron a que surgiera una Bohemia Negra en San Juan Hill. Músicos y bailarines como James y Rosamond Johnson, Harry T. Burleigh, Will Marion Cook, Bert Williams y Bob Cole acudían a la zona, y por las noches, en lugares como el Marshall, donde “había un ambiente alegre en el comedor”, con música en directo y “multitudes de hombres y mujeres de color bien vestidos que pasaban el rato charlando en los salones, con una taza de café y un cigarrillo mientras conversaban o escuchaban la música”, se percibía una enorme energía creativa.10 James Weldon Johnson afirmó que el Marshall acogió a la primera banda de jazz moderna que tocó en Manhattan. La orquesta, llamada Memphis Students, incluía una combinación de banjos, saxofones, clarinetes y tambores de claqué para crear un nuevo sonido.11

Aunque tanto los emigrantes como los inmigrantes admitían que en Nueva York acudían al culto con menos frecuencia que en sus países de origen, la iglesia seguía siendo el centro de la vida de la población negra. A medida que el barrio se expandía, también aumentaba la cantidad de instituciones que atendían a su población. Las iglesias Metodista Episcopal de San Marcos, Bautista de Monte Olivet y San Benito el Moro abrieron nuevos edificios al sur de San Juan Hill. Los portales de decenas de iglesias salpican el paisaje apelando a las costumbres particulares de los recién llegados del Sur y del Caribe. La Iglesia Bautista de la Unión, por ejemplo, dirigida por el reverendo Dr. George H. Sims, de Virginia, reunía a los “residentes más recientes de esta nueva e inquietante ciudad” y hacía que el cristianismo “cobrara vida el domingo por la mañana” con un servicio de “estilo sureño”. Llegó a ser conocida como la “iglesia de los gritos”. Del mismo modo, la Capilla de San Cipriano, una iglesia episcopal construida a principios del siglo XX en San Juan Hill, atraía a los fieles nacidos en el Caribe.12 Un domingo cualquiera, los visitantes podían ver los suntuosos trajes que llevaban los feligreses a los servicios. Según un testigo, predominaban los “guantes blancos y las ropas elegantes”. Los hombres negros solían llevar un traje oscuro, “zapatos derby negros, abrigos negros o marrones o gris oscuro, y en muchos casos… ¡hasta bastones!”. Las mujeres solían lucir vestidos de colores brillantes y sombreros elaborados.13

Además de satisfacer las necesidades espirituales de sus miembros, las instituciones religiosas también ofrecían oportunidades sociales con actividades como excursiones de verano fuera de la ciudad, picnics, conciertos y conferencias. Las iglesias ofrecían ayuda a los necesitados, estaban a la vanguardia de los esfuerzos por la justicia social y, a menudo, lideraban los esfuerzos para la mejora de la condición racial. Los párrocos intentaban a menudo intervenir ante los tribunales cuando los miembros de la iglesia se enfrentaban a procesos penales. Otros salían a las calles del barrio para predicar en contra de los vicios. Los ministros de la Iglesia Episcopal de San Cipriano y de la Iglesia Bautista de la Unión, ambas situadas en San Juan Hill, contribuyeron significativamente a la reducción de la cantidad de “antros y clubes” en la zona.14

Surgió una gran variedad de organizaciones para proporcionar apoyo y actividades sociales a los residentes negros del barrio. La YMCA abrió sus puertas al sur de San Juan Hill a finales del siglo XIX, para ofrecer un “hogar” para “todos los jóvenes del Sur… donde pueden venir y encontrar amigos”.15 La Grand United Order of Odd Fellows, la Colored Freemasons y la Negro Elks” también se constituyeron durante este período y establecieron sus sedes en el barrio. Los inmigrantes caribeños organizaron equipos de cricket y clubes de tenis, mientras que los sureños practicaron activamente el béisbol. Y mientras los forasteros blancos solían ver una población homogénea, los neoyorquinos negros resaltaban sus diferencias formando grupos como la Sociedad de los Hijos de Nueva York, los Hijos e Hijas de Carolina del Sur, los Hijos de Carolina del Norte, los Hijos de Virginia, la Asociación Benéfica de las Bermudas, la Sociedad de los Treinta Cubanos, la Sociedad Danesa de Ayuda a las Antillas y la Sociedad Progresista de Montserrat.16

Los pequeños comerciantes encontraron su nicho respondiendo a preferencias específicas de cada etnia. Los inmigrantes y los emigrantes buscaban recrear la sensación de hogar a través de la cocina, y tanto los restaurantes como las tiendas de comestibles ayudaban a satisfacer esos deseos. Rosanna Weston, residente de toda la vida en las Phipps Houses, una vivienda modelo para familias negras de clase trabajadora que abrió sus puertas en West 63rd Street, en el corazón de San Juan Hill, a principios del siglo XX, recuerda la cocina de su madre inmigrante. “Había un par de comerciantes de color en nuestro edificio que vendían cosas de las Indias Occidentales”, contaba, “entre ellas, harina de maíz y bacalao, ingredientes poco comunes en las tiendas de comestibles estadounidenses”. Su madre preparaba una comida llamada “fungie”. “A mí no me gustaba demasiado”, admite Weston, “pero la comíamos muy a menudo”.17 Asimismo, los restaurantes solían ofrecer comidas especiales con delicias sureñas o caribeñas, como la acelga con batata, aprovechando la nostalgia y la añoranza para aumentar la clientela.18

La vida del barrio también se caracterizaba por la hostilidad de las comunidades blancas de los alrededores. Las vías abiertas del Ferrocarril Central de Nueva York, “que mutilaban a blancos y a negros por igual”, ofrecían un terreno neutral entre los residentes negros y los “enemigos blancos” del oeste. Los padres de Rosanna Weston le advirtieron que se alejara del lado irlandés de la calle. “Aquel era un territorio prohibido. No debíamos acercarnos por allí. Solían cruzar de este lado y causaban peleaban”.19 Pero era casi imposible evitar la violencia. Un informante anónimo escribió al alcalde Mitchell en 1914 para quejarse de “un grupo de chicos blancos” que recorrían el distrito exigiendo dinero a cualquier transeúnte negro. Si se negaban a pagar, recibían una reprimenda física; una mujer recibió un golpe en la cabeza con una botella de leche.20

El racismo y el hostigamiento de los blancos hicieron que los neoyorquinos negros aprendieran a confiar los unos en los otros, y eso fue precisamente lo que hicieron en su comunidad de San Juan Hill. Los vecinos ayudaban a los vecinos: cuidaban mutuamente de sus hijos, abrían sus casas a las personas que necesitaban un lugar para dormir y se solidarizaban con quienes tenían problemas. Los desconocidos se convirtieron rápidamente en parientes ficticios, que ofrecían consejos sobre los misterios de la vida en la ciudad y un oído amable cuando la soledad se apoderaba de ellos. Los recién llegados del sur y del Caribe establecieron sus hogares “entre caras conocidas”, ayudando a crear enclaves discretos dentro de las abarrotadas calles de San Juan Hill. “Un ama de casa que cuelga tímidamente su ropa en el tejado su primera mañana de lunes en Nueva York se complace en descubrir que, en la siguiente soga, se balancea la ropa de una conocida de Richmond, que la instruye en los desconcertantes dispositivos de limpieza de su piso”, escribió Mary White Ovington. “Encontrar a la chica que conociste en casa, en el banco de al lado, es aún más encantador cuando has llegado cansado y con nostalgia, a la gran ciudad de Nueva York”.21 De esta manera, los negros recién llegados a Nueva York recrearon un sentido de hogar y construyeron un lugar de pertenencia en la ciudad de acogida. Pero fue la increíble diversidad de la comunidad de San Juan Hill, con su miríada de lenguas, herencias, ideas y tradiciones, la que ayudó a despertar el ingenio creativo que pronto produciría el Renacimiento de Harlem y convertiría a la ciudad de Nueva York en la capital cultural de la América negra.

1 Marcy S. Sacks, Before Harlem: The Black Experience in New York City before World War I (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), p. 6.

2 Gilbert Osofsky, Harlem: The Making of a Ghetto. Negro New York, 1890–1930, 2nd ed. (New York: HarperCollins, 1971), pp. 3, 8.

3 Frances Blascoer, Colored School Children in New York (New York: Public Education Association of the City of New York, 1915), p. 75.

4 Seth Scheiner, Negro Mecca: A History of the Negro in New York City, 1865-1920 (New York: NYU Press, 1965), pp. 15–19.

5 Mary White Ovington, Half a Man: The Status of the Negro in New York (1911; reprint New York: Hill and Wang, 1969), p. 22.

6 J. Gilmer Speed, “The Negro in New York,” Harper’s Weekly 44 (December 22, 1900), pp. 1249–50.

7 Mary White Ovington, Black and White Sat Down Together: The Reminiscences of an NAACP Founder, ed., Ralph E. Luker (New York: CUNY Press, 1995), p. 26.

8 Clyde Vernon Kiser, From Sea Island to City: A Study of St. Helena Islanders in Harlem and Other Urban Centers (New York: Columbia University Press, 1932), p. 164.

9 Sacks, Before Harlem, pp. 186–87.

10 James Weldon Johnson, Along This Way: The Autobiography of James Weldon Johnson (New York: The Viking Press, 1933), pp. 171, 172.

11 Roi Ottley and William J. Weatherby, The Negro in New York: An Informal Society History, 1626–1940 (New York, Oceana Publications, 1967), p. 157.

12 W. E. B. DuBois, The Black North in 1901: A Social Study (New York: Arno Press, 1969), pp. 16–17; Sacks, Before Harlem, pp. 6, 180.

13 Sacks, Before Harlem, pp. 180, 184.

14 Sacks, Before Harlem, p. 184.

15 Silas Xavier Floyd, Life of Charles T. Walker, D.D. (Nashville, 1902), pp. 108–9; Scheiner, Negro Mecca, pp. 15-19; Osofsky, Harlem, pp. 12–13.

16 Sacks, Before Harlem, p. 192.

17 Jeff Kisseloff, You Must Remember This: An Oral History of Manhattan from the 1890s to World War II (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989), p. 197.

18 Sacks, Before Harlem, p. 174.

19 Kisseloff, You Must Remember This, p. 190.

20 Sacks, Before Harlem, p. 80.

21 Ovington, Half a Man, pp. 26-27.

1 Marcy S. Sacks, Before Harlem: The Black Experience in New York City before World War I (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), p. 6.

2 Gilbert Osofsky, Harlem: The Making of a Ghetto. Negro New York, 1890–1930, 2nd ed. (New York: HarperCollins, 1971), pp. 3, 8.

3 Frances Blascoer, Colored School Children in New York (New York: Public Education Association of the City of New York, 1915), p. 75.

4 Seth Scheiner, Negro Mecca: A History of the Negro in New York City, 1865-1920 (New York: NYU Press, 1965), pp. 15–19.

5 Mary White Ovington, Half a Man: The Status of the Negro in New York (1911; reprint New York: Hill and Wang, 1969), p. 22.

6 J. Gilmer Speed, “The Negro in New York,” Harper’s Weekly 44 (December 22, 1900), pp. 1249–50.

7 Mary White Ovington, Black and White Sat Down Together: The Reminiscences of an NAACP Founder, ed., Ralph E. Luker (New York: CUNY Press, 1995), p. 26.

8 Clyde Vernon Kiser, From Sea Island to City: A Study of St. Helena Islanders in Harlem and Other Urban Centers (New York: Columbia University Press, 1932), p. 164.

9 Sacks, Before Harlem, pp. 186–87.

10 James Weldon Johnson, Along This Way: The Autobiography of James Weldon Johnson (New York: The Viking Press, 1933), pp. 171, 172.

11 Roi Ottley and William J. Weatherby, The Negro in New York: An Informal Society History, 1626–1940 (New York, Oceana Publications, 1967), p. 157.

12 W. E. B. DuBois, The Black North in 1901: A Social Study (New York: Arno Press, 1969), pp. 16–17; Sacks, Before Harlem, pp. 6, 180.

13 Sacks, Before Harlem, pp. 180, 184.

14 Sacks, Before Harlem, p. 184.

15 Silas Xavier Floyd, Life of Charles T. Walker, D.D. (Nashville, 1902), pp. 108–9; Scheiner, Negro Mecca, pp. 15-19; Osofsky, Harlem, pp. 12–13.

16 Sacks, Before Harlem, p. 192.

17 Jeff Kisseloff, You Must Remember This: An Oral History of Manhattan from the 1890s to World War II (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989), p. 197.

18 Sacks, Before Harlem, p. 174.

19 Kisseloff, You Must Remember This, p. 190.

20 Sacks, Before Harlem, p. 80.

21 Ovington, Half a Man, pp. 26-27.

If you have questions about the media featured on this site, please email [email protected].

Top image courtesy of: NYC Parks Photo Archive

Si tiene preguntas sobre los medios que aparecen en este sitio, envíe un correo electrónico a [email protected].

Traducido al español por GoDiversity.com.

Imagen superior por cortesía de: Archivo fotográfico de NYC Parks