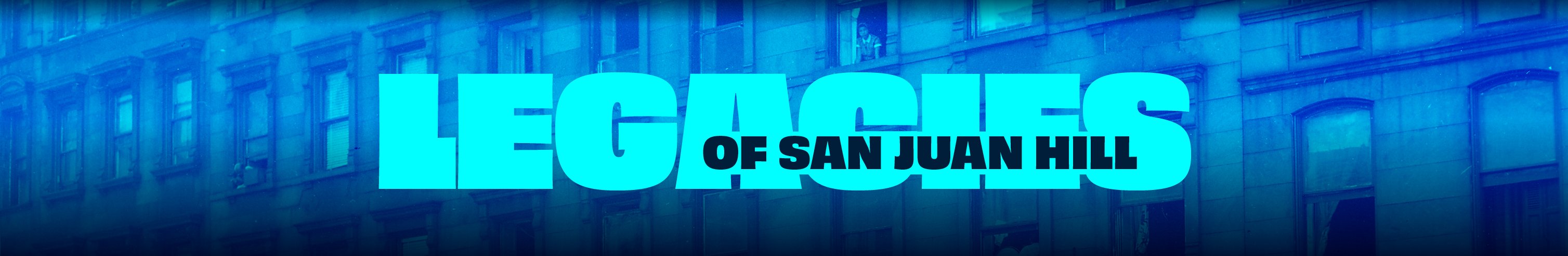

Millie Donay and Pedro 'Cuban Pete' Aguilar dancing the Mambo at the Palladium ballroom in the film Mambo Madness.

Photo: Yael Joel/The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Latin Jazz and San Juan Hill

Latin Jazz and San Juan Hill

November 17, 2023

by Chris Washburne, Musician, Author, and Professor of Music at Columbia University

In the latter half of the 20th century, the name “Latin jazz” emerged as genre and marketing label for any jazz blended with the musics of the Caribbean and Latin America. The label served to publicly acknowledge the Caribbean and Latin American contributions to jazz, but also segregated the music into a sub-genre of jazz thereby ignoring the rich intercultural roots of the music. Musics from the Caribbean and Latin America have shared a common history with jazz, intersecting, cross-influencing, and at times seeming inseparable, as each has played a prominent role in the other’s development. New Orleans, with its unique cultural climate and close historical ties to the Caribbean and Latin America, served as a central node of jazz innovation playing key roles in fostering these cross-cultural relationships from the music’s beginnings. The repertoire, performance practice, and rhythmic underpinnings of early jazz were largely influenced by Caribbean and Latin American music traditions, so much so that early musicians did not conceive of these traditions as separate entities and openly acknowledged their foundational connection. Most noted is pianist Jelly Roll Morton, who proclaimed, “If you can’t manage to put tinges of Spanish in your tunes, you will never be able to get the right seasoning, I call it, for jazz.”1 In this context, “Spanish” refers to music coming from Spanish speaking regions of the Caribbean and Latin America. With his “Spanish tinge” comment, Jelly Roll Morton acknowledged the significant influence that “other” musics of the New World exerted on jazz, thereby embracing the notion of jazz as a creolized mode of expression where two distinct yet closely related narratives of the Black Atlantic2 are conjoined, that of the Black Caribbean and Black America (North, Central, and South). Morton was not the first to comment on the Spanish tinge. In 1898, African American composer Benjamin Harney published a book titled Ben Harney’s Rag Time Instructor. In the introduction, he stated: “Ragtime or Negro dance time originally takes its initiative steps from Spanish music, or rather from Mexico, where it is known as… Habanera, Danza, Seguidillo…”3 And in 1938, bandleader Duke Ellington commented: “When I came into the world, Southern Negroes were expressing their feelings in rhythmic ‘blues’ in which Spanish syncopations had a part.”4

New Orleans is the key historical link connecting what I conceive of as a “Black archipelago,” which extended north along the Mississippi River to Chicago, spreading across the United States, and extending down to the far reaches of South America, all by way of the Caribbean.5 This Black archipelago served to nurture and perpetuate the influential role of Caribbean and Latin American music in jazz throughout the 20th century. New York City eventually replaced New Orleans as a central node for jazz innovation and neighborhoods such as San Juan Hill became vibrant interfaces of multicultural close contact within the Black archipelago. This article explores the seminal role that San Juan Hill played in the development of Latin jazz.

From the 1890s to the 1910s San Juan Hill was one of the fastest growing Black neighborhoods in United States.6 Segregation policies in the US, with its reductive white/Black racial binary, greatly limited housing possibilities for all people of color, no matter where they came from or how they self-identified. This resulted in San Juan Hill becoming one of the City’s most diverse neighborhoods with a uniquely broad ethnic, racial, and economic mix. Many of its residents emigrated from the Caribbean.7 Like New Orleans, it was a cosmopolitan milieu that fostered close contact and intercultural mixing of diasporic Black populations from the Americas and the Caribbean. With its growing population came a vibrant music scene, which was referred to as “Black Bohemia,” with performance spaces, clubs, bars, and dance halls, such as the Jungles Casino and Marshall Hotel, that catered to a Black clientele and featured “Spanish-tinged” pre-jazz and early jazz styles.8 The venues served as early conduits for introducing the newest Black dance and music trends into the City (many of which were dance musics rooted in the Caribbean and Latin America, such as the Cuban habanera and danzón, and the Argentine tango). San Juan Hill’s resident musicians and clubs were central to the development of Black diasporic expressive culture in New York City.

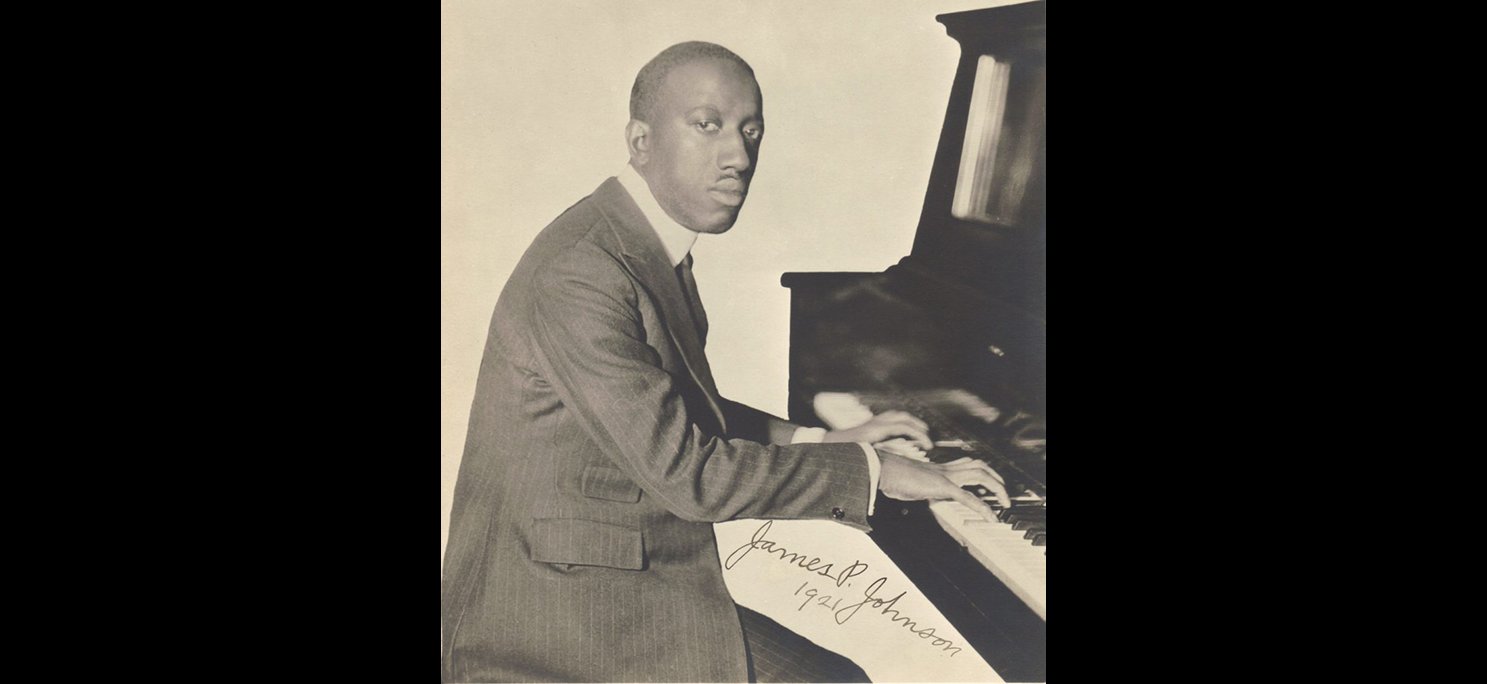

One of the most well-known and influential music developments emerging from San Juan Hill came by way of pianist James P. Johnson and his work at Drake’s Dancing Class, a basement dance-hall commonly referred to as the Jungles Casino. Located close to the docks on West 62nd street, this venue catered to local working-class patrons coming from a wide range of Afro-diasporic places and often featured solo pianists. Stride piano innovator and composer Johnson performed there regularly. As a lone musician performing for a diverse crowd, he had to attend to a wide range music styles and dances during his sets. He recalls how the demand of the dancers at the Jungles Casino led to a dance craze that transformed popular tastes around the world.

“The people who came to the Jungles Casino were mostly from around Charleston, South Carolina, and other places in the South. Most of them worked for the Ward Line as longshoreman or on ships that called on southern coast ports. There were even some Gullahs among them. The Charleston, which became a popular dance step on its own, was just a regulation cotillion step without a name. It had many variations—all danced to the rhythm that everybody knows now. It was while playing for these southern dancers that I composed a number of Charlestons—eight in all—all with the same rhythm. One of these later became my famous “Charleston” when it hit Broadway."9

Pianist Willie “The Lion” Smith adds:

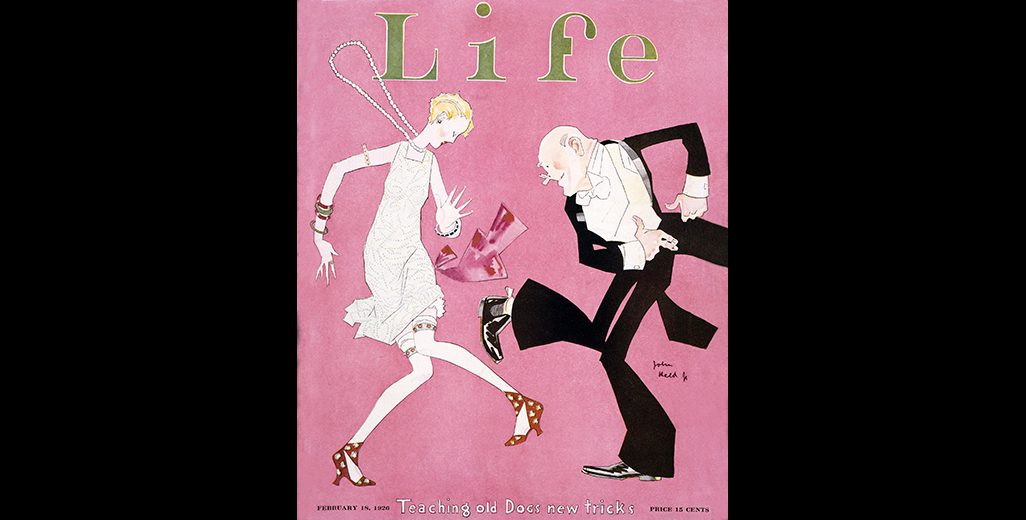

“The Gullahs would start out early in the evening dancing two-steps, waltzes, scottishces ; but as the night wore on and the liquor began to work, they would start improvising their own steps and that was when they wanted us to get-in-the-alley, real lowdown. It was from the improvised dance steps that the Charleston dance originated. All the older folks remember it became a rage during the 1920s and all it really amounted to was a variation danced at the Casino and this usually caused the piano player to make up his own musical variation to fit the dancing.”10

The two beat Charleston rhythm has its roots in West African traditions and was brought to the New World by enslaved peoples. In the 19th century, variations of the dance and rhythm were prominent throughout the Caribbean and southern United States. Like so many of the dance crazes of the 20th century, the rhythmic foundations tended to be rooted in shared Afrodiasporic practices. Though Johnson and Smith credit the Gullah people’s dance traditions, this rhythm resonated with Afro-Caribbean dancers as well, ensuring wide popularity and proliferation. This example aptly demonstrates the process in which a localized tradition from marginalized communities, can resonate widely through networks of mass mediation, in this case being featured in the Broadway show Runnin’ Wild and through music recordings and sheet music publications. Moving from improvisatory steps of dancers in a basement club in San Juan Hill to mainstream popular culture within just a few years is a remarkable feat, and a model that was adopted by the recording industry to launch every single dance crazed that followed, many coming from Black traditions of the Caribbean. This example aptly captures the immense influence that the Black archipelago exerted on popular culture and the key to understanding the popularity of Latin Jazz styles among a wide range of audiences around the world.

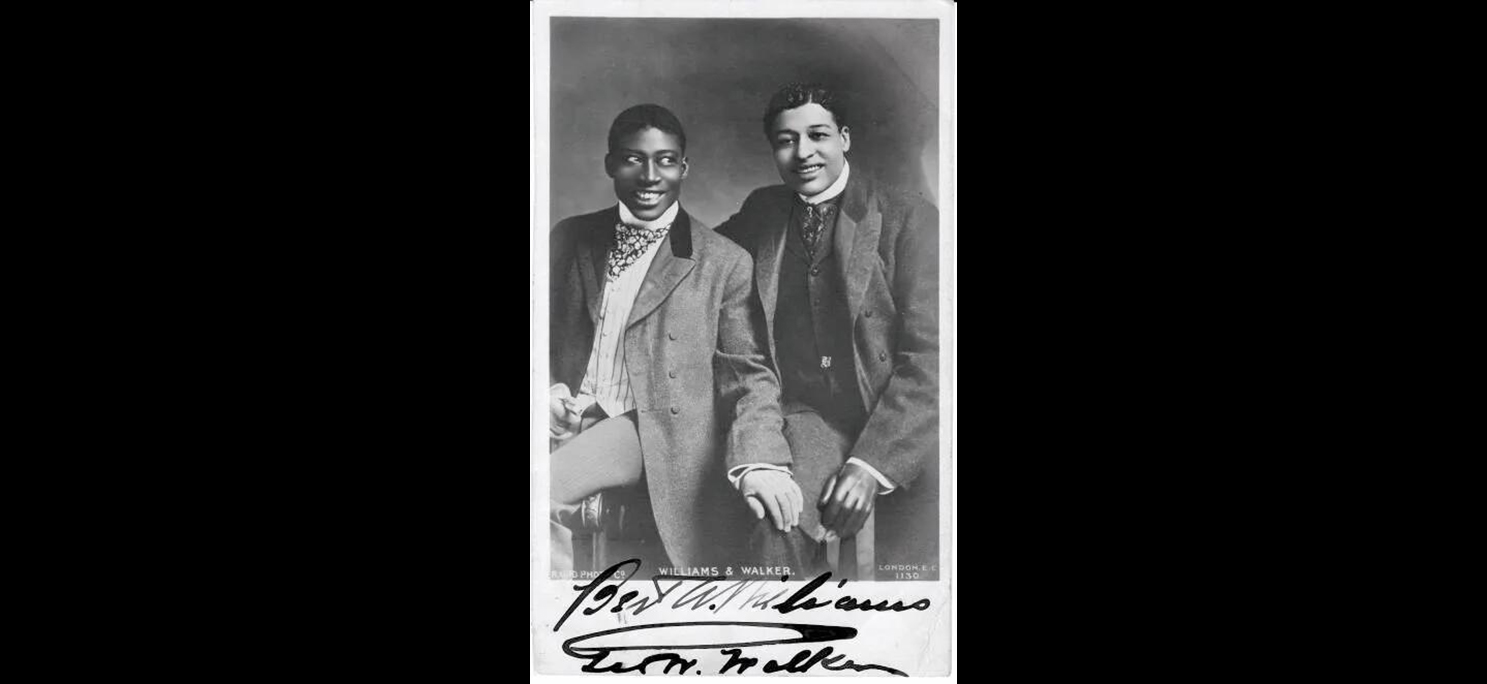

The Marshall Hotel, located just to the south of San Juan Hill on West 53rd Street, was an upscale venue that was frequented by prominent Black intellectuals, politicians, celebrities, and artists listening to the most well-known Black performers. Entertainers Bert Williams and George Walker, writer James Weldon Johnson, composers Will Marion Cook and J. Rosamond Johnson, prize fighter Jack Johnson, and musicians Eubie Blake and James Reese Europe frequented the Hotel. It was the place where the most influential and accomplished residents of San Juan Hill socialized. Though only open from 1900-1913, its influential reach was vast. It was the only desegregated club in midtown where Black and white patrons from the highest echelons of society intermingled on the dance floor, foreshadowing the diversity found at the Palladium Ballroom of the 1950s and serving as a model for Harlem’s famous Savoy Ballroom. And more importantly, the interchange of ideas among the Black artistic and intellectual community at the Marshall laid the groundwork for what would become known as the Harlem Renaissance.11

The cultural mix of San Juan Hill had a profound impact in the conversations at the Marshall. James Reese Europe was the most prominent bandleader of Black music in New York City, playing ragtime and other pre-jazz and proto-jazz styles. During conversations over dinner at the Marshall with other prominent Black musicians the idea was formed to found the Clef Club, an organization that served as a Black musician’s union, booking agency, advocacy coalition, and served as a home for the Clef Club Orchestra, a large 125-piece orchestra dedicated to performing Black music. In 1910, the Clef Club was opened across the street from the Marshall Hotel, and Europe served as its first president and conductor of the orchestra.12 He debuted his orchestra at Carnegie Hall in 1912, the first instance of Black music performed at the Hall. The concert featured W. H. Tyers “Panama” (1912), an early pre-jazz composition with a prominent Cuban habanera beat—an early example of what would become known as Latin jazz.

The concert was a benefit for the newly established Music School Settlement For Colored People located at West 63rd Street in the heart of San Juan Hill. The pupils were primarily neighborhood kids and the school was dedicated to instilling a strong commitment to Black diasporic musics in the next generation of Black musicians.13 In 1917, when drafted to recruit the 369th Regiment (Colored) military band (later known as the Harlem Hellfighters), Europe traveled to Puerto Rico to enlist close to half the band. From his experiences with the resident musicians of San Juan Hill, he knew Puerto Rican musicians tended to be conservatory trained thus able to read music well, a necessary skill in his military band. When the band traveled to Europe, the collection of African American and Afro-Puerto Rican musicians became the first to introduce “Spanish-tinged” pre-jazz and early jazz styles to foreign audiences. At the end of the war, a number of the Puerto Rican musicians, including the famous trombonist and composer Raphael Hernandez, stayed in New York performing with the top Black jazz bands of the 1920s and 30s and influencing the development of Latin jazz in New York City for many years to come.14

The Marshall Hotel closed in 1913 as more strict segregation policies were enforced in Midtown. The Black population of San Juan Hill began moving uptown to Harlem establishing a new center for Black cultural innovation in New York City. However, the influence of the “Black Bohemia” of San Juan Hill continued to resonate for years serving as precursor and model to the Harlem Renaissance as well as impetus for the development of Latin jazz.

****

The close intercultural relationships established in San Juan Hill are key to understanding the popularity of the Latin music dance crazes, such as the rhumba, conga, mambo, cha cha, and salsa, among African American audiences in Harlem. For instance, since its opening in 1934, the Apollo Theater in Harlem was considered the most significant venue in the twentieth century for African American music and dance. Ted Fox, chronicler of the venue, contends that “the Apollo probably exerted a greater influence upon popular culture than any other entertainment venue in the world. For Blacks it was the most important cultural institution— not just the greatest Black theatre, but a special place to come of age emotionally, professionally, socially, and politically.”15 Studying the historical narratives concerning the theater’s history and traditions, one might surmise that Caribbean and Latin American performers rarely graced that hallowed stage. Their presence is completely absent in a discourse that is informed by a narrow US-based perspective of Blackness. But between the years 1948 and 1965, Cuban bandleader Machito and his Afro-Cubans performed fourteen one-week engagements, and Nuyorican bandleader Tito Puente performed ten one-week engagements. Duke Ellington’s band, on the other hand, played only nine one-week engagements during that same period.16 The popularity of Caribbean and Latin American music among Black audiences was forged in San Juan Hill. The programming of the Apollo Theater throughout the 20th century was a manifestation of the Black archipelago and the intercultural exchange advanced in San Juan Hill.

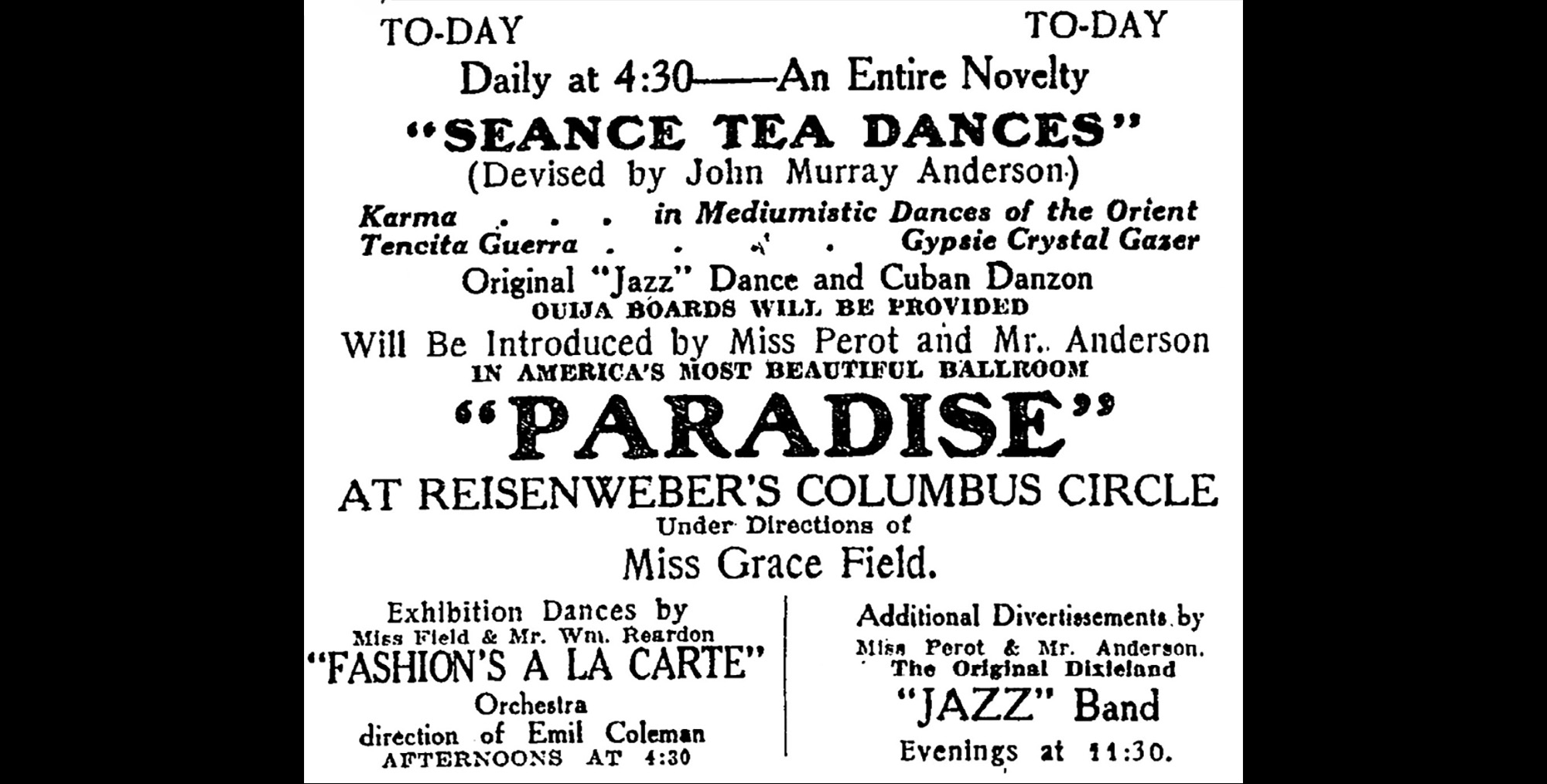

Some of the most significant and paradigm shifting performances in Latin jazz history, happened just on the borders of San Juan Hill. This was not pure coincidence. The multi-cultural mix of Black culture emulating from within the confines of San Juan Hill resonated with the growing fascination (some might say fetishization) with performed “exotic otherness” among white audiences in surrounding New York City neighborhoods. The exotica in vogue focused on staged primitivism and Blackness, the roots of which can be traced to the influence of the World’s Fair (Exposition Universelle) exhibitions of 1889 in Paris and the Primitivist artistic movements that emerged in its aftermath in the 1910s and 1920s.17 The artwork of Georges Braque, André Derain, Amedeo Modigliani, and others; the popularity of Josephine Baker in Paris; and the “jungle” music of Duke Ellington performed at the Cotton Club in New York for white audiences are just some of many manifestations of this phenomena. Starting in the 1910s, dances from “other places” grew in popularity among white audiences. The figure below shows an advertisement from The New York Times for the Paradise Ballroom at Reisenweber’s Columbus Circle from March 9, 1917, a club which stood in the location where Jazz at Lincoln Center now resides. The event was titled “Seance Tea Dances” and promises “An Entire Novelty,” with activities that include “Gypsie crystal gazing,” Ouija boards, and introduction of “the Original ‘Jazz’ Dance and the Cuban Danzón” accompanied by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band (ODJB), the first recorded jazz band made up of white musicians from New Orleans. This is one of the earliest examples of a U.S. jazz group playing Cuban music in New York City, and it happened right on the border of San Juan Hill.

Though many of the earliest performances were racist and imbued with exoticized fantasy, some performers were able to capitalize on the opportunities in entrepreneurial and creative ways. Many Cuban performers were particularly adept at staging “otherness,” “Blackness,” and “primitivism” for the wave of visiting tourists in Havana seeking an authentic Cuban experience. Some performers took advantage of that experience when traveling abroad to gain a foothold on international touring circuits. One such artist was Don Justo Angel Azpiazú. On April 26, 1930, Don Azpiazú and his Havana Casino Orchestra were invited to perform at the RKO Palace Theater, located just blocks from San Juan Hill on Broadway and 47th Street. Azpiazú was one of the first bandleaders to develop equal competence in Cuban music and jazz styles. He expanded the traditional Cuban conjunto (typically a sextet or septet) to a fourteen-piece big band (modeled on the Fletcher Henderson band, one of the most successful New York jazz bands of the 1920s). And he was one of the first bandleaders to employ a multiracial band both in Cuba and in the U.S. His performance at the Palace Theater marked one of the first occasions when a racially integrated band performed in New York at an exclusively white venue. Because the band identified as Cuban, the band’s “otherness” enabled them to skirt segregation laws banning white and black musicians appearing on stage together. Within in a few years, many racially integrated bands started to perform in New York City. Azpiazú was central in making that possible by setting the precedent.

Azpiazú’s recording of “El Manisero” (“The Peanut Vendor”), was released shortly after the concert. “The Peanut Vendor” was the best-selling recording of 1931, becoming the first recording in Spanish and first by a foreign artist to reach #1 in the U.S. Its meteoric rise launched the “rhumba” dance craze (a precursor to the conga, mambo, cha cha, and salsa dance crazes). Within a matter of weeks, numerous jazz and pop stars recorded their own versions, such as the California Ramblers, Red Nichols, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and Paul Whiteman.18 Azpiazú’s concert and subsequent recording altered the history of Latin jazz.

Another significant moment in Latin Jazz history occurred on September 29, 1947 at Carnegie Hall, located a few blocks from San Juan Hill. Trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie’s Band was invited to perform a concert billed as “A Program of the New Jazz.” For years prior, Gillespie had developed a deep love for Cuban music due to his close friendship with Cuban trumpeter Mario Bauzá. He took the opportunity of his Carnegie Hall debut as a bandleader to commission composer George Russell to write the “Afro Cuban Drum Suite” featuring an extended conga drum solo performed by Cuban percussion Chano Pozo. As one of the inventors of bebop, a music that sought to disrupt the jazz tradition by infusing issues of race, revolution, high art, intellectualism, and virtuosic individualism to unprecedented higher degrees, Gillespie was deeply invested in exploring his cultural roots through his music. He found the public embrace of their African heritage and lineage by Afro-Cuban musicians inspiring and refreshing, and he felt that Cuban traditions mixed with jazz offered a viable option for sounding out the Black archipelago and a shared circum-Atlantic Black experience. As such, his performance avoided the trite exotica stagings of the past and instead embraced the wide array of rich Afro-Cuban traditions respectfully. The Gillespie and Pozo collaboration revitalized the Caribbean and Latin American influence in jazz, amplifying the reverberations of its past influence. Trumpeter Wynton Marsalis concurs: Gillespie “didn’t just represent what’s modern… the greatest artists have a dialogue with the entire history of the form, not just with those aspects that are prevalent in their particular time… It’s like the Latin music he was into – that’s always been in jazz.”19

The Palladium Ballroom, located at Broadway and West 53rd Street just south of San Juan Hill, opened in 1948 programming Cuban and Puerto Rican dance bands playing mambo—the newest Latin dance craze. The midtown club attracted an overwhelming and unprecedented number of African American patrons, along with Latine and white dancers. The audiences at the Palladium crossed racial, class, and ethnic divides in unparalleled ways.

The promotors capitalized on this cross-cultural popularity and began exclusively programming the best Latin dance bands led by Arsenio Rodriguez, Machito, Tito Rodriguez, and Tito Puente. Catering to an integrated crowd, the Palladium broke down years of audience segregation and established the first truly integrated dance floor in the United States. This level of desegregation, even in the earliest years of the Civil Rights Movement, reflected the profound influence of culture exchange fermenting for many years prior in neighborhoods like San Juan Hill. The Palladium can be seen as a manifestation of the daily life lived in San Juan Hill and a microcosm of what the future of the United States would become.

Even though the neighborhood has drastically changed over the last 135 years, San Juan Hill’s unique cultural mix still reverberates within its environs, nurturing vital connections of a globalized identity within the Black archipelago, especially through performances of Latin jazz. The Jazz at Lincoln Center programming, under the direction of Wynton Marsalis, has produced a number of Caribbean and Latin American themed concerts each season. Some examples include “The Latin Tinge: Jazz Music and the Influence of Latin Rhythms” featuring Tito Puente the Fort Apache Band, and Arturo Sandoval in March 1995 and “Afro-Cuban Jazz” featuring Chico O’Farrill’s Afro-Cuban Jazz Orchestra in November 1995. From 2002–2007, pianist Arturo O’Farrill directed the Lincoln Center’s Afro-Latin Jazz Orchestra. More recently, Cuban clarinetist Paquito D’Rivera and Nuyorican bassist Carlos Henríquez have led numerous Latin jazz performances at the Rose Theater and at Dizzy’s Club Coca Cola. By acknowledging the intercultural exchange of Black culture in San Juan Hill during the formative years of Latin jazz, we capture the nuance and richness of the music’s past, where the complexities involved in the relationships of race, ethnicity, nation, and place are revealed as central to the music’s foundation.

Notes

1 Jelly Roll Morton, The Complete Library of Congress Recordings (Rounder Records (1938) 2005).

2 Paul La Chance, “The 1809 Immigration of Saint- Domingue Refugees,” in The Road to Louisiana: The Saint- Domingue Refugees, 1792- 1809, edited by Carl Brasseaux and Glenn R. Conrad, 245– 284 (Lafayette: Center for Louisiana Studies, University of Southwestern Louisiana 1992), p. 259.

3 John Storm Roberts, Latin Jazz: The First of the Fusions, 1880s to Today (New York: Schirmer 1999), p. 10.

4 Edward Kennedy Ellington, “Music Is ‘Tops’ to You and Me… and Swing Is a Part of It,” Tops (1938), pp. 14, 18.

5 Christopher. Washburne, (Latin Jazz: the Other Jazz. Oxford University Press 2020), pp. 90-112.

6 Gilbert Osofsky, Harlem: The Making of a Ghetto. Negro New York, 1890–1930, 2nd ed. (New York: HarperCollins, 1971), pp. 3, 8.

7 Marcy S. Sacks, Before Harlem: The Black Experience in New York City before World War I (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), p. 6

8 James Weldon Johnson, Along This Way: The Autobiography of James Weldon Johnson(New York: The Viking Press, 1933), pp. 171, 172.

9 Franklin Bruno, “James P. Johnson: From ‘Carolina Shout’ to ‘The Charleston’.” Sound American. (https://soundamerican.org/issues/alien/james-p-johnson-carolina-shout-charleston).

10 Bruno, “James P. Johnson: From ‘Carolina Shout’ to ‘The Charleston’.”

11 Marc Kirkeby, “The Brightest Days of the Marshall.” NYC Department of Records & Information Services (April 20, 2017), (https://www.archives.nyc/blog/2017/4/20/the-brightest-days-of-the-marshall).

12 Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library. "“Clef Club”" The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1940. (https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/63c91170-712d-0133-8f1a-00505686a51c).

13 Carnegie Hall Rose Archives. Complete program of Clef Club Orchestra: Concert of Negro Music, May 2, 1912. (https://collections.carnegiehall.org/archive/Clef-Club-Orchestra--Concert-of-Negro-Music--May-2--1912-2RRM1T8ICS48.html).

14 Tomas Peña, “Honorry Boricua Pioneer James Reese Europe (1881-1919), (April 5, 2019). (https://jazzdelapena.com/puerto-rico-project/james-reese-europe-honorary-boricua-pioneer/).

15 Ted Fox, Showtime at the Apollo: 50 Years of Great Entertainment from Harlem’s World- Famous Theater. (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston 1983), p.4.

16 Washburne, Latin Jazz: the Other Jazz.

17 Glenn Watkins, Pyramids at the Louvre: Music, Culture, and Collage from Stravinsky to the Postmodernists (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press 1989) and Glenn Watkins, Soundings: Music in the Twentieth Century (New York: Schirmer 1995).

18 Cristóbal Díaz Ayala, Cuando sali de la habana 1898– 1997: Cien años de musica cubana por el mundo (San Juan: Fundación Musicalia, 1999).

19 Howard Mandel, “Remembering Dizzy: All Dizzy’s Children,” DownBeat 60 (April 1993), pp. 25– 26.